Historian

The Historian/Archivist maintains the Archive of the Society which comprises:

- Standing Rules

- Guidelines

- Committee and General Business Meetings

- Scientific Meetings

- Newsletters and Information Bulletins

- Membership lists

- Accounts/Treasurer’s Reports

- Nominating Committee

- Liaisons with other societies

- J. Neurochem. Editorial Board

- Transfer of the Journal from Pergamon to Raven Press (subsequently Lippincott), and then to Blackwell Science

- Photographs and memorabilia

- History of ISN

- Correspondence on the archive

- Miscellaneous

The material in most of the above categories is supplied to the Archive by officers of the Society, but other members are invited to submit, for example, photographs, obituaries of neurochemists and biographical and historical articles of an appropriate nature that they may have published.

The Historian/Archivist also promotes interest in the history of both the Society and of neurochemical topics in general by organising historical sessions at ISN meetings and by other activities. He welcomes suggestions from members.

Introduction

The original desire for this history arose from the realisation that the Society was reaching its 25th. Birthday and the intention was that the then I.S.N. historian (Henry McIlwain) would write it. His response to that invitation was that he would be pleased to do so, in co-operation with myself and with the help of Elizabeth Bock. His untimely death resulted in the task being delegated to Elizabeth and myself. As we discussed it, we quickly became aware that there had to be a choice between a multi-author compilation of the views and recollections of those intimately involved in the affairs of the Society or to try to present a cohesive account written by one person. Therefore the account which follows must perforce be a personal one and does not reflect the views of the past or present Officers of the Society. I have tried to present a lively history which reflects the spirit and feelings of those great men who generated what has now become a vital and successful Society, rather than a chronicle of events.

An eminent English historian (A.J.P. Taylor) observed, in his Origins of the Second World War, that no objective history can be written until at least 25 years after the events – I hope the account which follows is faithful to that principle. I (with a great amount of help from friends and colleagues listed below) have checked the sources as thoroughly as I can, but the early records remain incomplete, despite the efforts of our historians to collect and collate them for the I.S.N.archives. “The history of the world is but the biography of great men” (Thomas Carlyle) – perusing the archives serves to confirm this. Minutes and anecdotes are written by individuals to the best of their notes and recollections, and the records attributed to different individuals about the same incidents reflects their own sometimes differing personal interpretations. I have tried to present a balanced account of the times when the development of the Society was sometimes stormy but usually peaceful and constructive, and am grateful to the following colleagues for responding to requests for anecdotes, recollections, memorabilia and photographs : Bernie Agranoff, Alan Boulton, Frode Fonnum, Tim Hawthorne, Les Iversen, Graham Johnston, Elling Kvamme, Abel Lajtha, Henry McIlwain+, Paul Mandel+, Derek Richter, Donald Tower and Victor Whittaker. I am grateful also to Tim Hawthorne for his constructive comments, to Elizabeth Bock for her comments and help in organising the manuscript, and to Professor Graham Collingridge for allowing easy access to Henry McIlwain’s archives at Birmingham during his illness and after he passed away. Apart from the archives, I have drawn on the historical articles of Folch-Pi (1980) McIlwain (1985, 1990, 1991), Page (1937) and Tower (1958, 1981,1987) .

The first history of the Society was Jordi Folch-Pi’s summary of its origins and activities which were included in the Membership Directory of 1979-80. Unfortunately, he died just before it appeared and it has been reproduced in modified and updated form in 5 succeeding Membership Directories. A more detailed history of the I.S.N. was written to commemorate its first 20 years by Henry McIlwain (1985). Although this is a history of an academic society, there were many earlier threads which generated the need for such a society and are therefore described briefly.

+Sadly two of them died during the writing of this history.

Chapter 1 – Before the Beginning

The ideas and concepts of the ancients, through to the anatomists and physiologists of the 17th. and 18th. Centuries which provided the foundations for man's motives in understanding the metabolism of nervous systems, and the more biochemical approaches in the 19th. Century, have been detailed in Donald Tower's most enjoyable and scholarly historical articles (Tower, 1958, 1981). Indeed for anyone interested in the development of the subject, these are highly recommended.

The 1981 article appeared originally as the Introductory Chapter to the 3rd edition of a textbook (Basic Neurochemistry), sponsored by the American Society for Neurochemistry (A.S.N.), but unfortunately, space forbade its inclusion in subsequent editions. As Tower points out, the first chemical analysis of the brain can probably be attributed to J.T. Hensing, who isolated phosphorus. His book on “The Chemical Analysis of the Brain” published in Giessen in 1719 was translated into English by Tower in 1983. Although Thudichum is often regarded as the “father of Neurochemistry”, the term “Nervenchemie” had been coined by Schlossenberger in the 1850s, well before Thudichum’s treatise appeared in 1884. Neurochemistry, such as it was then in the latter half of the 19th. Century, tended to be dominated by organic chemists – analytical chemists like Thudichum seemed antagonistic to the contributions of physiological chemists such as Schlossenberger . The dominance then of organic chemistry over physiological chemistry (which quickly became synonymous with biochemistry) meant that the biological orientation which could have stimulated neurochemistry was essentially ignored. In some countries, the rapid development of biochemistry in the first decades of this century led to an integration of neurochemistry with biochemistry. In others, it remained constrained by organic chemists (see McIlwain, 1990, 1991).

J. Folch-Pi

H. McIlwain

Around the turn of the century, Garrod had suggested that certain diseases could be caused by inherited disorders of specific metabolic processes, and in the 1930s Following demonstrated that phenylketonuria, a disease with severe effects on the newborn brain, was an example of Garrod’s principle. In the 1920s and 1930s people were bravely pioneering the investigation of the biochemistry of the nervous system : Gerard, Himwich, Page and Sperry in the U.S.A., Dale, Peters, Quastel and Thompson in the U.K., Klenk and Winterstein in Germany and Palladin in the then U.S.S.R. Indeed neurochemical research was often at the forefront of the biochemistry of the 1920s to 1950s, especially with increasing insight into metabolism and metabolic regulation, and was stimulated by the writings of pioneers such as Winterstein (1929), Page (1937), Richter (1944), Himwich (1951) and Peters (1952).

McIlwain regarded 1955 as the coming of age of neurochemistry – that year saw publication of the book which resulted from the first International Neurochemical Symposium (Table 1), the publication of a collation of 32 neurochemical contributions (Elliott et al., 1955), the publication of the first specifically neurochemical textbook (McIlwain, 1955) and the gathering of the manuscripts for the ensuing first issue of the Journal of Neurochemistry.

In the years immediately after the second world war, almost 50% of hospital beds in developed countries were occupied by mental patients and were seen to be increasing. This was clearly due to improvements in the treatment of physical ailments (antibiotics, immunisation and surgery) rather than treatment of psychiatric disorders which remained intractable. Much of the impetus for the growing interest in neurochemistry stemmed from the realisation that many neurological and especially psychiatric disorders may be largely “organic” in origin, and therefore likely to have a biochemical basis. Neurochemistry was relatively unfashionable in those days, mainly because the prevailing opinion was that the brain was far too complex for its chemistry to be studied effectively. However some of the early symposia of Table 1 focussed on deranged metabolism and were sponsored or generated by bodies such as the Mental Health Research Fund (M.H.R.F.) of the U.K. Concern over the high incidence of recognised mental diseases had resulted in the foundation of the M.H.R.F. in London as early as 1949; its Honorary Secretary was a neurochemist, Derek Richter. Some of the key early investigations of human brain metabolism were initiated by psychiatrists in the U.S.A., epitomised by the pioneering studies of Kety and his colleagues in the late 1940s. The key seminal and specifically neurochemical conference held in 1965 in Oxford (Table 1) was held under the auspices of the Commission of Neurochemistry of the World Federation of Neurology (W.F.N.).

First International Neurochemistry Meeting – Oxford

The second World War had stimulated a massive acceleration of scientific research, and many historians have argued that the outcome of that war was directly correlated with the quality of the scientific and technological developments. Accordingly, there was a rapid expansion of all of the sciences in the post-war era, which included a major impetus to the development of neurochemical research. (It is a sad reflection on human affairs that it takes the bestiality of war to provide the impetus and resources for basic scientific research!). Neurochemistry benefitted, as did biochemistry in general, from the availability of new techniques and instruments. Indeed, Tower (1981) is of the opinion that it was essentially the availability of the new, techniques which enabled neurochemistry to emerge as a, distinct discipline. Many of our younger colleagues may not realise that chemicals such as ATP and NAD+, and all enzymes, had to be isolated and purified manually in the laboratory (none were commercially available then) and that acetyl CoA had not yet been characterised, is then identified as “active C-2 unit,” or “active acetate”. Techniques such as electrophoresis, ultracentrifugation, chromatography and radiochemistry were under development; radioimmune assays and “molecular biological” techniques had not even been envisaged.

D. Tower

Chapter 2 – The Beginning

There were many unrelated threads which contributed to the eventual fabric of the I.S.N. In addition to the activities of the M.H.R.F. (from 1949) and the World Federation of Neurology (W.F.N., established in the 1950s), the first International Congress of Biochemistry (forerunner of the International Union of Biochemistry, I.U.B.) was also held in 1949 in London and included neurochemical contributions. Discussions amongst Japanese scientists at a meeting in 1958 led to the formation of the first neurochemical society, the Japanese Society for Neurochemistry, in 1962.

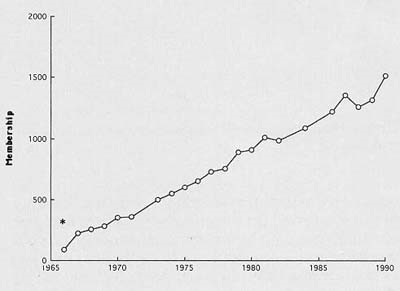

Parallel threads were the attention given to neurochemistry by the American Academy of Neurology in 1957 (Tower, 1958) and the regular meetings of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum, initiated in Rome in 1958 (McIlwain, 1985). Neurochemical themes were thus appearing in national and international symposia organised by biochemists, neurologists and psychiatrists; these seemingly disparate activities generated a growing realisation that the subject needed a forum specifically its own. So the idea of forming some sort of international forum for neurochemistry began to be discussed in the late 1950s by those principally involved in the early neurochemical symposia listed in Table 1. These informal discussions stimulated a letter from Jordi Folch-Pi and Heinrich Waelsch in May 1962 to potential supporters, suggesting the formation of a Provisional Organising Committee (P.O.C.), which was set up in 1963. At about the same time Derek Richter approached Pergamon Press to enquire about the possibility of the copyright of the previously established Journal of Neurochemistry being transferred to the new society, once it had been founded. Membership of the P.O.C. had truly international representation, drawn essentially from the scientists who’d been prominent in the early symposia ( Folch-Pi, U.S.A.; Hyden, Sweden; Klenk, Germany; McIlwain, U.K.; Mandel, France; Palladin, U.S.S.R.; Pope, U.S.A.; Richter, U.K.; Rossiter, Canada; Takagaki, Japan and Waelsch,U.S.A) . Each member of that committee was asked to nominate ten names as potential members of the new society – these names were collated in 1965 by Folch-Pi and the total list sent to the members of the committee, who voted. Each nominee needed two votes – a surprising number failed to obtain the 2-vote support. The final number approved was 79, which with the 11 members of the P.O.C. gave a total original membership of 90. The correspondence of the time (1964 to 1965) reveals considerable disagreement on the criteria required for membership. Derek Richter argued for membership is open to all those actively interested in neurochemistry. In a letter (archives) to Warren Sperry in November 1964, he gave his view that the society “would gain more than it could lose by extending its membership to anatomists, physiologists, pharmacologists, neuropathologists and neurologists with active neurochemical interests”. Unfortunately, this sane and liberal view did not prevail at the time, and the outcome restricted membership to established neurochemists with little encouragement for young scientists or active investigators in closely-related disciplines. A careful reading of the correspondence of the time gives a clear impression of fears of domination by “research-naive” clinicians. Fortunately, these misgivings did not persist for long as witnessed by the healthy and productive collaborations between clinicians and basic scientists that we now enjoy. Yet it was perceived as a real problem at the time. The outcome then was that the criteria were intended to restrict membership to those who had clearly established themselves as dedicated professional neurochemists (i.e. by having published three full neurochemical papers). The P.O.C. met in London in 1965, a few days before the Oxford meeting (Table 1), and announced its establishment during that meeting. The Officers and Council were quickly elected by postal ballot of the members, and new members were solicited by announcements which resulted in membership of 226 by July 1967. Growth was slow over the first years but started to accelerate in the early 1970s (Fig. 1).

- D. Richter

- H. Waelsh

- P. Mandel

- R. Rossiter

Table 1: Major Neurochemical Symposia preceding the formation of ISN

|

Year |

Venue |

Publication |

|

1950 |

New York |

“The Biology of Mental Health & Disease” Milbank Conference, Hoeber, New York, 1952 |

|

1951 |

London |

“Metabolism & Function in Nervous Tissue” Biochem.Soc.Sympos. 8 ,1-102, 1952 (ed. R.T.Williams) |

|

1952 |

Bristol |

[This was arguably the first truly International Neurochemical Meeting, organised by Derek Richter under the auspices of the newly-formed Mental Health Research Fund. A book was proposed but not published. It was at this meeting that the idea of regular international symposia was formalised] |

|

1952 |

Oxford |

“Prospects in Psychiatric Research” Blackwell, Oxford, 1953 (ed. J.M. Tanner) |

|

1954 |

Oxford |

“Biochemistry & the Developing Nervous System” * Acad. Press, New York, 1955 (ed. H. Waelsch) |

|

1955 |

Atlantic City |

“Neurochemistry” Progr. Neurobiol. I, 1956 (ed. S.R. Korey & J.I. Nurnberger) |

|

1956 |

Aarhus |

“Metabolism of the Nervous System” * Pergamon, London, 1957 (ed. D. Richter) |

|

1958 |

Vienna |

“Biochemistry of the CNS” Pergamon, New York, 1959 (ed. F.Brucke) |

|

1958 |

Strasbourg |

“Chemical Pathology of the Nervous System” * Pergamon, London, 1961 (ed. J. Folch-Pi) |

|

1958 |

Philadelphia |

“The Neurochemistry of Nucleotides & Amino Acids” Wiley, New York, 1960 (ed. R.O.Brady & D.Tower) |

|

1959 |

Duarte |

“Inhibition of the Nervous System & g-Aminobutyric acid” Pergamon, New York, 1960 (ed. E.Roberts et al) |

|

1960 |

Varenna |

“Regional Neurochemistry” * Pergamon, London, 1961 (ed. S.S. Kety & J. Elkes) |

|

1962 |

Goteborg |

“Enzymic Activity of the Central Nervous System” Acta Neurol. Scand. 38, Suppl.1, 1962 |

|

1962 |

St. Wolfgang |

“Comparative Neurochemistry” * Pergamon, London, 1964 (ed. D. Richter) |

|

1965 |

Oxford |

“Variation in Chemical Composition of the Nervous System as determined by Developmental & Genetic Factors” Pergamon Press, London, 1966 (ed. G.B. Ansell)+ |

* These meetings were designated International Neurochemical Symposia 1 to 5 respectively; these earlier meetings were by invitation only and limited to ca. 100 participants (McIlwain, 1985; Tower, 1987) It was immediately before this meeting that the ISN was founded.

Note: scientists of the former U.S.S.R. organised a series of symposia on “Biochemistry of the Nervous System” in Kiev (1954 & 1957), Yerevan (1962), Tartu (1966), Tblisi (1968) and Leningrad (1972).

Figure 1. The numbers are total members, including Emeritus, Sustaining and Junior members, since the records do not always list these categories separately. When listed, full members were ca. 80% of the total. The fall in members in the mid-1980s was apparent rather than real: Frode Fonnum commented that it was due to improved membership lists which avoided duplication. * Original invited members.

During this period (1965) Henry McIlwain and Derek Richter drafted the statutes for the new society, and after some modifications, these were formalised in July 1967 as the Articles of Association by the London solicitors, Adam Burn & Metson.

The proposed name of the fledgeling society differed amongst the interested parties – thus we see letter-heads in 1964-1966 giving the title variously as “International Society of Neurochemists”, “International Society of Neurochemistry” and “International Neurochemical Society”. Our current title was first mentioned in correspondence in 1966 and was well accepted by the time the Society was formed.

The Society quickly built on its gestation by organising the biennial International Meetings which began in Strasbourg in 1967 and continue to flourish (Table 2). Earlier meetings had a central theme, often but not always of clinical significance; the subject has now grown to the size that this is no longer possible. So many different specialities have to be included that numerous concurrent symposia and workshops have become inevitable. The Program Committee recognised the rapid and highly specialised growth of neurochemistry by organising a series of “state of the art ” educational lectures in plenary sessions. One major function of international meetings is the informal discussions over coffee or a beer, particularly instructive to younger scientists, a feature which has been recognised in the travel grants now available.

[One of our recent Officers, Bernie Agranoff, has expressed his appreciation of these meetings with a treatise on the cultural and gastronomical delights of the venues in his personal recollections, preserved in the Archives].

In the early days, Abel Lajtha suggested the possibility of holding Satellite meetings on specialised topics at around the time of the main meeting. While there was some concern that these might interfere with the attendance at the meeting, the Council agreed, and they were very successful. Over the ensuing years, the number of Satellites grew, some of which were held in places remote from the main meeting. As a result of this increase, the policy with regard to Satellite meetings began to cause some concern, because there were some meetings where a considerable proportion of participants attended Satellites but not the main meeting. This is understandable because financial support is usually easier to find for small specialised meetings on a specific theme than for general meetings.

Nevertheless, the I.S.N. exists essentially to promote the dissemination of neurochemistry, and if experts in specialised topics do not attend the main meetings, this rather defeats the object of the exercise! So the Council and Organising Committee in the run-up to the Nottingham meeting stressed the desirability of holding Satellites in the host country and preferably after the main meeting. While this is clearly desirable, it is usually difficult to ensure. Nevertheless, the Satellites continue to make an important contribution to the interchange of ideas on specific circumscribed topics.

Table 2: Biennial ISN Meetings

|

Venue |

Year |

Participants* (active) |

Host |

|

|

1. |

Strasbourg |

1967 |

300 |

P. Mandel |

|

2. |

Milan |

1969 |

R. Paoletti |

|

|

3. |

Budapest |

1971 |

600 |

S.Huszak & J. Szentagothai |

|

4. |

Tokyo |

1973 |

700 |

Y. Tsukada |

|

5. |

Barcelona |

1975 |

800 |

J. Sabater |

|

6. |

Copenhagen |

1977 |

766 |

J. Clausen |

|

7. |

Jerusalem+ |

1979 |

880 |

S. Gatt |

|

8. |

Nottingham |

1981 |

830 |

J.N. Hawthorne |

|

9. |

Vancouver |

1983 |

1200 |

E. & P. McGeer |

|

10. |

Riva del Garda |

1985 |

865 |

G. Tettamanti |

|

11. |

La Guiara@ |

1987 |

750 |

M. Laufer |

|

12. |

Albufiera |

1989 |

1100 |

A. Carvalho |

|

13. |

1991 |

Sydney |

833 |

G. Johnston |

|

14. |

1993 |

Montpellier |

M. Recasens |

+Discussions in Council on preparations for the meeting about possible insurance against disruption due to war!

* Often, only about 25-30% of the active participants were ISN members, which has caused concern in Council according to the minutes.

@ Joint meeting with A.S.N., which according to George Hashim, attracted some 450 accompanying participants.

We all owe a tremendous debt to our founders (particularly Jordi Folch-Pi, Henry McIlwain, Derek Richter and Heinrich Waelsch) for their foresight in creating the Society and their wisdom in its implementation – indeed it is only when perusing the correspondence of the time that one can appreciate how much time and energy they expended. It is not obvious to us now how difficult it must have been then to achieve a solid and harmonious international society, given the national aspirations, rivalries and cultural differences of the various individuals involved. Their contribution is often overlooked, and it is fascinating to sense some of the feelings of the times we are describing, gauged from the minutes and correspondence available to us. As described above, the beginnings of I.S.N. were truly international – the great neurochemical pioneers who had established high-quality research centres in the 1920s to 1960s were identifiable particularly in the U.S.A. and the U.K., with France, Italy, Japan and Sweden. [There were also important developments in the then U.S.S.R., and in Eastern European countries such as the then East Germany (D.D.R.), Czechoslovakia and Hungary, but due to the “cold war” these were not easily appreciated elsewhere]. So one can say the major innovative developments in neurochemistry were taking place mainly in Europe and the U.S.A.

This was reflected in the origins of the society’s officers in the early years : the data of Table 3 show that from the years 1967 to 1981 the executive officers (Chair, Secretary and Treasurer) were 9 from the North Americas and 9 from Europe (in their differing capacities drawn from the U.K., 2; France, 1; Germany,1; Italy,1 and Norway,1). The “German” (Victor Whittaker) happened to be of British origin, so the development of the society tended to be weighted towards, perhaps dominated by, English speaking officers. In these times when the English language is the “lingua franca” of international communication generally, this can produce an insidious problem in international science, not only for the communication of science in learned journals but particularly in the organisation of international scientific societies. In the debates inherent in the deliberations of the Councils, Executive Committees and General Business Meetings of scientific societies, the ability to “think on one’s feet” is a major advantage to people speaking spontaneously in their own language – an advantage not acknowledged sufficiently frequently by native English speakers?

The minutes and correspondence of the first decade reveal considerable disquiet about the way the society was being run. It is indeed difficult to find the precise reasons for this disquiet – the main concerns seem to fall into two categories, expressed in diverse ways by different correspondents. The first, which has been a point of contention until relatively recently, was what was perceived as a rather cumbersome and bureaucratic method of approving new members and the criteria required were by no means universally accepted by existing members; and that in its early days, the running of the Society (clearly and explicitly expressed in the correspondence) could give the impression of being somewhat paternalistic, arbitrary and autocratic. The second was that there was so much activity in neurochemistry in many countries that some attention should be paid to regional Groups or Societies.

The dissatisfaction about accountability to the membership, and regarding the participation of members in nominating candidates for election as officers were eventually, then quickly, resolved as described below with the establishment by the Council in 1975 of the Nominations Committee (Table 3).

Table 3: Officers of the Society 1967 – 1991.

|

Year |

Chairman |

Secretary |

Treasurer |

PC |

MC |

CC |

NC |

FISN |

AHC |

PrC |

|

1967 |

Rossiter+ |

Folch-Pi |

Richter |

Cumings |

Mandel |

|||||

|

1969 |

Richter |

Folch-Pi |

Mandel |

Cumings |

Folch-Pi |

|||||

|

1971 |

Folch-Pi+ |

Lajtha |

Mandel |

Richter |

Rossiter |

Cumings+ |

Paoletti, Folch-Pi |

|||

|

1973 |

Mandel+ |

Lajtha |

Ansell |

Tower |

Dahlstrom |

Riekkinen |

Tsukada |

|||

|

1975 |

Lajtha |

Aprison |

Ansell |

Tower |

Dahlstrom |

Svennerholm |

Whittaker |

Folch-Pi |

||

|

1977 |

Ansell+ |

Aprison |

Kvamme |

Sokoloff |

Dahlstrom |

Blass |

Whittaker |

Heilbronn |

Lajtha |

Sources |

|

1979 |

Aprison |

Porcellati |

Kvamme |

Wolfe |

Dahlstrom |

Blass |

Rodnight |

Johnston |

Lajtha |

Agranoff |

|

1981 |

Kvamme |

Porcellati |

Boulton |

Wolfe |

Kurakawa |

Blass |

Rodnight |

Johnston |

Lajtha |

Fonnum |

|

1983 |

Porcellati+ |

Whittaker |

Boulton |

Wolfe |

Kurakawa |

Rodnight |

Johnston |

Kvamme |

Shooter |

|

|

1985 |

Boulton* |

Whittaker |

Agranoff |

Suzuki |

Kurakawa |

Cuenod |

Kvamme |

Winkler |

||

|

1987 |

Hawthorne** |

Fonnum |

Agranoff |

Suzuki |

Zimmermann |

Tettamanti |

Boulton |

Hamprecht |

||

|

1989 |

Agranoff |

Fonnum |

Suzuki |

Norton |

Zimmermann |

Tettamanti |

Hawthorne |

Morell |

||

|

1991 |

Fonnum |

Bock |

Suzuki |

Norton |

Zimmermann |

Lunt |

Agranoff |

Livett |

+Since deceased, *Acting Chairman after Guiseppi Porcellati’s death in 1984, **Tim Hawthorne replaced Victor Whittaker as Secretary between 1986 and 1987

PC: Publications Committee; MC: Membership Committee; CC: Clinical Committee; NC: Nominations Committee (for elections of Officers and Council Members); FISN: Future of IS

Chapter 3 – Relations between I.S.N. and other Societies

As noted above, well before the formation of I.S.N., neurochemistry had had representation in the meetings of organizations such as the Mental Health Research Fund (M.H.R.F.) established in 1949, the World Federation of Neurology (W.F.N.), established in the mid 1950s, and the International Brain Research Organization (I.B.R.O.) from the early 1960s.

The M.H.R.F. had as its first secretary a neurochemist (Derek Richter), and a neurochemist (Heinrich Waelsch) was the first Treasurer of I.B.R.O. And subsequently, it’s Secretary. The W.F.N. formed a Commission of Neurochemistry in 1959, of which the first Secretary was the Belgian neurochemist, Armand Lowenthal. These societies had thus an active neurochemical input, which is reflected perhaps in the initiative for the first I.S.N. conference in Strasbourg (1967) emerging from a joint meeting between the Provisional Organizing Committee of I.S.N. and the W.F.N. Commission of Neurochemistry.

So the birth of I.S.N. had M.H.R.F., I.B.R.O. And W.F.N. as enthusiastic mid-wives!

With this history of generous support from these world bodies, the newly-formed I.S.N. seems to have been curiously reluctant to encourage regional neurochemical activities in various parts of the world. During a N.A.T.O. Conference in Milan in September 1970, there were sufficient members of the I.S.N. Council present to hear representations from Alan Davison and Brian Ansell on behalf of the British Neurochemical Group (established in 1967 – see Bachelard, 1988) and from the representatives of the Swedish-Italian Neurochemical Group (Hyden & Paoletti), suggesting the formation of some form of a European neurochemical group or society. The I.S.N. Council actively discouraged any such development, even though the newly-formed American Society (A.S.N.) was flourishing. Then in 1971 Roger Marchbanks and Alan Davison made a formal written proposal for a federal structure for neurochemical societies, with I.S.N. remaining as the main focal point for meetings and international activities, but also acting as the central co-ordinating body. The view of the I.S.N. Council was against federation because it felt it “could inhibit the development of neurochemistry in less well-developed countries and that single individual would be cut off from participating in the activities of I.S.N.”. This appeals as an eminently reasonable view, but there is no record in reports or minutes of any further debate or discussion. Indeed the only relevant comment in the minutes at that time was a refusal to consider the nomination of a candidate for membership of I.S.N., because “neurochemistry was not of sufficiently high quality in his country”. This reads now as quite odd in view of the above-stated support for individuals. In a letter sent by the Secretary to members of I.S.N. Council, dated Dec. 22, 1970, he argued against federation, and the formation of regional societies, with the comment that “at the time neurochemistry has not reached the degree of development at which the establishment of a European society would be realistic”. This gives some idea of the parochialism of the time (long since disappeared), when the majority of the early International Neurochemical Symposia had been held in Europe and initiated by Europeans (11 of the first 16, Table 1), when over 40% of the papers published in J.Neurochem. came from that part of the world and from where at least half of the elected I.S.N. officers had originated (Table 3). Indeed of the 24 papers published in the first volume of the journal, 11 were from the U.S.A. and Canada, with 13 from European contributors. The I.S.N. Council minutes of the time recorded opposition to the formation of regional societies, but set up an informal committee to “Promote Neurochemistry in Europe” consisting of Davison, Hyden, Mandel & Paoletti, to report back to the Council at the Budapest meeting in 1971. This was communicated to members in the I.S.N. Bulletin of 1970, but no further discussion is recorded in the minutes. Obviously all this resulted in mounting disquiet in the perceived accountability of the officers to the general membership and particularly in the mechanisms for the nomination of the officers. Accordingly, there was a considerable amount of acrimonious discussion at the General Business Meeting in 1971 in Budapest (in fact to those not directly involved it was highly entertaining), but no further action appears to have been considered then by the Council. However in the minutes of Council meetings of 1973, there was some discussion of the possibility of forming “local chapters” of I.S.N. – proposed for Canada, England, Italy, Japan, U.S.A. and the then U.S.S.R., but scrutiny of succeeding minutes reveals no further comment. Shortly after the foundation of the E.S.N. in 1976 (Bachelard, 1988), the E.S.N. Secretary submitted a further discussion paper on federation to the I.S.N. Council. In this paper the idea was advanced that neurochemistry had developed to the extent that it needed a world structure – that the I.S.N. should act as the central co-ordinating body (an “umbrella”) with regions representing the Americas (A.S.N.), Europe (E.S.N.) and anticipating the formation of a “Pan-Asian” S.N. (recently formed in 1992 as the A.P.S.N.) The response of the Council to this suggestion is not clear as no mention of it appears in the minutes, but shortly afterwards the I.S.N. Council approved the appointment of liaison members with E.S.N. (Alan Davison), A.S.N. (Bill Norton), E.N.A. (European Neuroscience Association, Edith Heilbronn) and the American Society for Neuroscience (Saul Berl ).

- M. Aprison

- F. Fonnum

Further activity in promoting liaison between relevant societies came in 1979 with suggestions from W.F.N. (Sir John Walton and Armand Lowenthal) that I.S.N., A.S.N. and E.S.N. might each nominate one member (with a further member nominated by W.F.N.) to serve on the Research Committee of the W.F.N. and to contribute to W.F.N.’s funds as subscribing corporate members. Copies of this correspondence are held in the Archives, but I could find no follow-up correspondence. E.S.N. held some joint symposia with W.F.N., and I.S.N.’s Clinical Committee earlier took pains to ensure clinical representation in the International Meetings, but both of these initiatives seem to have lost momentum. This is a great pity in that one of the main objectives of I.S.N. should be to contribute to the understanding and treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Indeed these motivations largely generated its beginnings as noted above, but seem to have been submerged in the understandable excitement of the major recent basic scientific advances in the neurosciences.

Chapter 4 – Growth of Neurochemistry as a Scientific Discipline

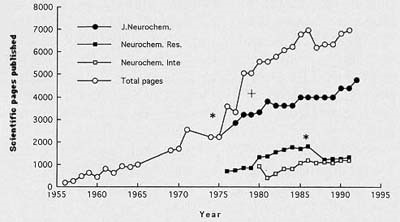

Some measure of the growth of the subject as an independent scientific discipline can be seen in the increase in membership of I.S.N. (Fig. 1) and in the increase in the pages published in the major journals devoted specifically to neurochemistry (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The growth of neurochemical journals. * The numbers of pages are distorted to some extent in that J. Neurochem. (in 1976) And Neurochem. Res. (in 1987) changed the format to obtain increased numbers of words per page. + Change of publisher

The Society was still rapidly evolving in the early 1970s with financial problems largely associated with the difficulties with Pergamon Press over publication of the journal (below), so it was not an easy time for the officers. Nevertheless, many members felt the organisation of the society still to be too paternalistic and autocratic with little opportunity for ordinary members to contribute to society affairs or to have any influence in the appointment of officers. These feelings were widespread and resulted in more open leadership, especially with the creation of a Nominating Committee under the guidance of Victor Whittaker. This was particularly important in providing a mechanism for direct participation by the members in a choice of candidates as nominees for the elections of Officers. Victor, in his personal recollections (archives) says “I felt that the procedures for the election of Officers and Councillors could be better organized. This led to the formation of the Nominating Committee in 1975. I was its first Chairman. This was an influential committee as it had the task of recommending to the Council suitable candidates for vacancies in the Officers and Council who, if approved, became official nominees. Care was taken, however, not to infringe the rights of members to make nominations of their own according to the Articles of Association”. A further improvement was introduced for the 1989 elections in that two official nominees (rather than one) for the posts of Secretary and Treasurer were on the ballot paper.

The Officers at that time put a great amount of effort in restructuring the Society with the formation of the Subcommittees listed in Table 3 (see also below). As the society grew and increased its business and pastoral activities, members of Council found that participation in the meetings, not only of Council but particularly of the myriad but valuable committees and subcommittees that had been set up, inhibited or sometimes prevented the (usually senior) scientists from attending the scientific sessions. The problem was exacerbated as members of Council were often on Councils of sister societies or members of the editorial boards of neurochemical journals, who took the opportunity to meet during I.S.N. meetings, taking advantage of cost-saving and the likelihood of a majority attendance. The Council took this matter seriously and for the Riva del Garda meeting, set up for the first time an I.S.N. office at the meeting with prescheduled timetables for all the various meetings to be held. The Council also began to meet before and after the scientific programme to enable members to contribute to the science, so important to the education of younger scientists. An important benefit from the new wealth was the ability to pay the extra expenses incurred.

The membership numbers increased slowly but steadily from 226 in 1967 to around 1500 now (Fig. 1). Exact numbers have sometimes been difficult to obtain as the reports to Council (to judge from the minutes) often listed applications, and the decisions on acceptance of new members, but not an update on current numbers, taking into account lapsed or deceased members. Also, if numbers were given, it was usually the total number, rather than broken into categories: full, associate, junior, emeritus, sustaining. At the time of the changeover from Pergamon to Raven as publisher of the Journal (because the publishers operated membership subscriptions on our behalf), there were considerable difficulties in knowing the precise membership : the Treasurer had 3 lists – one from Raven (incomplete initially because Pergamon refused to divulge it, section 8), the second from the I.S.N. Secretary and the third, his own. All different! It took much time and effort to establish a reliable membership list, mainly due to the labours of Victor Whittaker and Bernie Agranoff, noted below.

The procedure for processing applications for full or associate membership remained cumbersome, involving nomination by a Membership Committee for approval by Council, which met only every two years. If the timing wasn’t fortuitous, it could take much more than two years. The minutes of Council meetings from 1969 regularly included painful discussions about this, but it was only in 1977 that the procedure was streamlined, so taking approximately one year. It is still somewhat bureaucratic and tends to inhibit full voting membership of younger neurochemists, neuroscientists and clinicians genuinely interested in neurochemistry, but who have not published specifically on the subject or worked actively in it. Yet the society is anxious to increase its membership! The annual subscription for full members has risen very little over the past 25 years – originally $ 5 in 1967, it was increased to $ 10 in 1971-2, to $15 in 1973-4 and to $ 30 in 1980-1, which is the current subscription.

In 1978 the Society recruited some sustaining members who generously agreed to make a regular donation to support its activities: Merck Sharp & Doehm, Hoffmann LaRoche, EndoLabs and CIBA-Geigy. By 1981 they had been joined by Cyanamid, FIDIA, Glaxo, Merrell, Sandoz and Upjohn. There have been some changes since then, and the current sustaining members are CIBA-Geigy, FIDIA, Marion Merrell Dow, Merck Sharp & Doehm, Sandoz and Upjohn.

Communication with members initially took the form of a personal report letter from the Chairman and appeared in 1968, 1970 and 1971. These were succeeded by “Newsletters to Members” which appeared 2 or 3 times per year and ultimately evolved into the current “ISN News” (Section 5), for which contributions from ordinary members are assiduously solicited. Copies of most of these are stored in the I.S.N. archives.

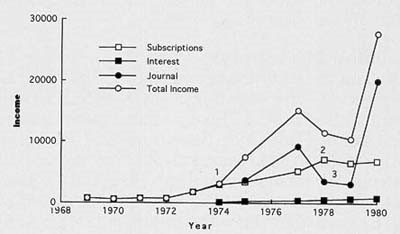

Chapter 5 – Finances

The income of the society originally depended solely on members' subscriptions, and after the agreement with Pergamon in 1970 this was supplemented by some £400 per annum until 1974. The contribution from Pergamon's assessment of the Society's share of journal profits fluctuated over the years from 1975 to 1980 and was usually between £3,000 and £10,000 (Fig. 3).

As described in section 8 it proved impossible for our Treasurers to assess what it should be. Pergamon paid the expenses of the two Editorial Offices and for an annual dinner for the combined Editorial Boards. It also solicited and collected I.S.N. membership subscriptions at no charge. Then with the new contract with Raven in 1980, the contribution to our finances from journal profits (nett, after editorial expenses) rose to £23,000 in 1981 and £84,000 in 1982, since when our nett profits have been running at well over £100,000 per annum.

On his election as Treasurer in 1973, Brian Ansell realised he had to re-organise the accounts completely, and at the end of 1973 he was confronted with the unpalatable fact that the annual financial returns had not been submitted to the U.K. Companies Registration Office for the 5 years from 1969 to 1973 – essential, if the I.S.N. were to retain its status as a registered company. He received a letter from the Registration Office threatening to dissolve I.S.N. as a Company and to strike it off the registry. This registration was a requirement not only for continuing as a business but vital in the forthcoming negotiations for obtaining Charitable Status. Henry McIlwain, as one of the Company Directors, received a letter informing him that he was liable to a personal fine of £5 per day until the returns were filed. This must have been disquietening, and he immediately contacted our solicitors who reassured him that he would not be personally liable. Presumably, the other Directors received similar missives, but of these, we have no record. They probably sensibly “binned” them immediately. Brian Ansell quickly got a stay of execution, and the matter was settled within weeks. The solicitors advised the Society that it was desirable for I.S.N. to have a Company Secretary, Brian being appointed in 1976 and succeeded by Tim Hawthorne. Charitable Status was approved in October 1977, which meant that the Society had to pay no tax on income or donations after that.

- G. Porcellati

- B. Ansell

By the end of 1973, Brian Ansell had restored a sound financial base with regular properly audited Treasurers reports, but the income was still low, due essentially to poor returns from the journal. This improved only in 1980-1 when true profit-sharing resulted from the new contract with Raven. During this period the $ was in trouble (1977-9) and then, as usual, the £ (1980-1). It was difficult for the Treasurer to decide where to bank the money! However the improved financial health eased this burden (Fig. 3), and in 1980-1, the Society was able to initiate travel grants, mainly for young scientists, due to a $10,000 donation from Pergamon Press (Section 8) and the income from the journal. Alan Boulton who became Treasurer in 1981, and subsequently Chairman, was particularly conscious of the new wealth of the society and the possibilities of implementing much-desired initiatives, as described in his personal recollections preserved in the Archives. The Society was also fortunate in benefitting from the generosity of the Italian pharmaceutical company, FIDIA, who due to the efforts on our behalf by Guiseppi Porcellati, subsidised our International Meetings with substantial grants for travel. By 1984, the nett share of the profit from the journal (i.e. after payment for editorial expenses) was running at such a level that there was now enough money to support small conferences also (Section 7). In 1991, awards for Young Scientist’s Lectures were initiated.

Figure 3.: Income (£) 1969-1980 (from Treasurer’s reports).1 In 1971-2 many subscriptions were not collected and were recouped in 1973.2 There was an intensive recruitment drive in 1977, related to streamlining of processing of membership applications (see text)

This represented (given fluctuations in the $/£ exchange rate), the minimum guaranteed profit from Pergamon, who stated that the journal then had been running at a loss. However, the Treasurers could not confirm this as they had no access to the publisher’s accounts (see text). Members’ subscriptions were $5 in 1969, increased to $10 in 1971-2, to $15 in 1973-4, and to the current rate of $30 in 1980-1. After 1980-1, income exceeded £100,000 p.a. due to journal profits, and since 1984, has been running at over £120,000 after editorial expenses had been paid.

Chapter 6 – I.S.N. as a Professional Business Organization

After completing his term as Chairman of the Nominating Committee in 1979, Victor Whittaker offered to organise the Membership Directory on a computerised basis. As noted above (Section 4) the precise membership was uncertain, so a considerable amount of correspondence was required to organise it satisfactorily. During his period as Secretary, he expended much energy in putting the Society's operations onto a sound professional, business footing, with rigorous attention to maintaining the membership list and to the publication of attractively-produced I.S.N. News and the Membership Directory.

It was not an easy task as three different membership files still existed: Victor’s directory, Raven’s Journal subscription file and Alan Boulton’s file on the acknowledgement of membership dues. Part of the problem arose from the fact that not all individual members subscribed to the Journal and it took considerable efforts by Alan Boulton and Bernie Agranoff to complete the final list. These files were finally organized into a master computer file by Bernie who then as Treasurer undertook responsibility for collection of both the membership dues and journal subscriptions, and initiated payment by credit card. For members fortunate in having credit cards this greatly facilitated payment in non-U.S. currencies and reduced the cost to the Society of currency conversions. The membership list is currently maintained by the Treasurer as he now receives the membership dues directly. At about this time the Solicitors observed that we were violating the Articles of Association by only having Business Meetings every two years, rather than annually as required. The Council then met more frequently at regular intervals, which though awkward since the full I.S.N. meetings were biennial, had the benefit of speeding up the approval of new members. Victor’s experience led him to suggest a formalisation of our business procedures with the establishment of a Business Office with a permanent Secretariat to help the Society to co-ordinate its various activities, which might also include journal business. [His detailed proposals can be read in an open letter to the members circulated with I.S.N. News in October 1986, preserved in the Archives]. However, the Council did not feel that a Business Office was an appropriate or necessary development at that stage. There was admittedly some friction between the Officers at the time, as there were quite different, and sometimes apparently irreconcilable, views on the best way forward for the Society. In such circumstances, the usual decision is not to change or interfere with a successful system, and await events. The Council took this decision and so far the Society proceeds in a healthy fashion. It may be that in the future the question of a Business Office will be reviewed again. The efficiency of the Society’s operations has been greatly enhanced by the installation of FAX facilities to enable Officers, Council members and Auditors to communicate freely and rapidly throughout its international operations. It has also enhanced communications between Publisher, journal editors and Council. All these developments, with the (sometimes painful) restructuring of the Society’s mode of operation, resulted in its organisation improving so much that it has become one of the most openly democratic of international scientific societies.

Chapter 7 – Further ISN Initiatives

The improved structure and financial state enabled the Society to create the numerous small Subcommittees, listed in Table 3. The first Subcommittees were the Clinical Committee (set up in 1967 for liaison with Clinical Neurochemists - since lapsed, see above), Membership Committee (1971) and the Nominations Committee (1975, for elections of Officers and Council Members).

The Future of I.S.N. Committee and the Ad-Hoc Committee were created in 1977. There was formerly a Public Affairs Committee, referred to in early Minutes, but no details could be found – it presumably arose to consider strategy and relations with the “outside world”. It seems to have been replaced by the Future of I.S.N. Committee in 1977. Abel Lathja’s recollections are that the F.I.S.N. emerged as a result of suggestions from Edith Heilbronn and Victor Whittaker for “significant changes in the Society’s function”. At about the same time the Ad-Hoc Committee was formed to provide continuity to I.S.N. policy, to consider new initiatives and to advise Council on the general policy of the Society. To benefit from the experiences of past Officers, it was designed to consist of past Chairmen, led by the most recently retired I.S.N.Chairman. The activities of these two Committees (F.I.S.N. and Ad-Hoc) were increasingly seen to be overlapping, so the F.I.S.N. Committee ceased to exist in 1985. The main function of the Ad-Hoc Committee (i.e. to advise Council on general policy) led some Officers recently to refer to it as the “Policy Advisory Committee”, but it remains listed in the I.S.N. News as the Ad-Hoc Committee.

A. Lajtha

The increased wealth of the Society after 1981 enabled it to implement some of its long-held objectives, especially to support the travel of young scientists to our biennial meetings. They were selected by the Officers until 1989 when the Travel Grants Committee was formed, chaired first by Elizabeth Bock and now by Pierre Morrell. The Treasurer of the time (Alan Boulton) was clearly delighted to be involved with these developments, as recorded in his personal recollections in the Archives. The Society was able also in 1984 to fund small specialised meetings and Lectureships: the Small Conferences Committee was chaired initially by Anders Hamberger and the Lectureship Committee by Nico van Gelder. In 1987 these were amalgamated into one Committee, chaired by Hans Winkler, who was succeeded by Bernd Hamprecht. Other Committees set up were a Placements Service to help young scientists find appropriate positions and a Professional Rights Subcommittee. The latter subcommittee (chaired by the author) experienced problems in defining its sphere of responsibility or its precise mandate – it was agreed that it could take up cases of infringements of professional human rights and freedoms of individuals rather than of groups and felt it could only realistically address the problems encountered by neurochemists. It finally expired due to the uncertainties of its role. The growing concern of many members over the difficulties being encountered by colleagues in many parts of the world (caused by political or economic problems) stimulated the Society, in partnership with Raven, to make available free copies of the Journal of Neurochemistry to selected recipients. This desire to provide scientific aid led rapidly to Council’s approval of Bernie Agranoff’s recommendation for the establishment in 1989 of the Committee for Deprived and Third-World Nations (chaired by Herminia Pasantes-Morales). There was some uncertainty as to the correct title for this committee, originally named the “Committee for Developing Countries”, with the idealistic motive of providing help to neurochemists in under-developed and deprived countries. The dilemma was that it was relatively straight-forward to identify third-world countries as under-developed or developing, but one could hardly regard politically or economically deprived countries such as e.g. Hungary or Czechoslovakia, as “developing countries”, with their rich history in, and contribution to, the sciences! So the current name (Committee for Deprived and Third World Nations) seemed the best compromise solution. The financial problems associated with recent events there may create difficulties comparable to those experienced by the truly under-developed countries. The committee has been very successful (with the generous support of Raven noted above) in identifying recipients of free subscriptions to the journal, and it is currently trying to identify ways of further help in terms of fellowships for training in new techniques, collaboration with neurochemists in more developed countries and supporting small conferences held in those countries where their scientists find it difficult to fund external visits.

Chapter 8 – Journal of Neurochemistry: Trials And Tribulations – and Success!

Robert Maxwell moved from his native Czechoslovakia to the U.K. at the outbreak of the Second World War. He served as an intelligence officer with the British Army, and so was quick to anticipate the post-war expansion of science described above, created Pergamon Press shortly after the war and published many of the early international neurochemical symposia, listed in Table 1.

One of his staff (Dr P. Rosbaud) was asked to contact Marthe Vogt in Cambridge to starting a new physiological journal. Marthe expressed more interest in a journal for neurochemistry and suggested that Dr Rosbaud contact Derek Richter, who furnished her with the names of eminent international neurochemists. She was met with enthusiastic responses from all she contacted. Part of that correspondence included a comment from Henry McIlwain which is worth reproducing: “The reputation of any journal, and to some extent of the subject itself, would be enormously dependent on an adequate editorial policy, which would probably be easier to maintain with a representative Editorial Board elected by or otherwise responsible to a Society” (letter to Dr. Rosbaud, 1965, archives). The title pages of the first issue of the journal are reproduced as Fig. 4.

Figure 4. First Cover of the Journal of Neurochemistry

It is to Pergamon’s credit that the original Editorial Board was fully supported in fulfilling those criteria. Also, it must be acknowledged that Pergamon never attempted to influence the scientific policy decisions of the Editors but kept control of pricing, format and page numbers. The correspondence of these first years exhibits a strong sense of harmonious relations between the Editors (Derek Richter and Heinrich Waelsch) and the publishers. For the first few years, the journal ran at a loss and was subsidised by the publishers. Early volumes contained some papers in French and German.

From the beginning, the Editorial Board was divided into two parts which still exist: a “Western Board” for papers submitted from North and South America, and an “Eastern Board” for papers from the rest of the world. Heinrich Waelsch and Derek Richter took responsibility for the two Boards and put an enormous amount of effort into ensuring high standards and helping authors get their papers published. The Western Board generally processed just over 50% of the papers, so the Eastern Board took responsibility for pastoral activities such as society notices, advertisements, book reviews and scientific reviews. Rejection rates and processing times were similar for the two Editorial Boards; relations were thus generally happy and constructive.

Table 4. Chief editors of the Journal of Neurochemistry

| Year | Eastern* | Western** |

|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Richter | Waelsch |

| 1957 | Richter | Waelsch |

| 1958 | Richter | Waelsch |

| 1959 | Richter | Waelsch/Sperry |

| 1960 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1961 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1962 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1963 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1964 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1965 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1966 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1967 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1968 | Richter | Sperry |

| 1969 | Richter | Tower |

| 1970 | Davison | Tower |

| 1971 | Davison | Tower |

| 1972 | Davison | Tower |

| 1973 | Davison | Tower |

| 1974 | Davison | Sokoloff |

| 1975 | Davison/Iversen | Sokoloff |

| 1976 | Iversen | Sokoloff |

| 1977 | Iversen | Sokoloff |

| 1978 | Iversen | Suzuki |

| 1979 | Iversen | Suzuki |

| 1980 | Bachelard | Suzuki |

| 1981 | Bachelard | Suzuki |

| 1982 | Bachelard | Norton |

| 1983 | Bachelard | Norton |

| 1984 | Bachelard | Norton |

| 1985 | Bachelard/Tipton | Norton |

| 1986 | Tipton | Lees |

| 1987 | Tipton | Lees |

| 1988 | Tipton | Lees |

| 1989 | Tipton | Lees |

| 1990 | Tipton | Boulton |

| 1991 | Tipton/Lunt | Boulton |

| 1992 | Lunt | Boulton |

** Responsible for the Americas, *responsible for the rest of the world. In addition to the above, many of whom were previously Deputy Chief Editors, the following have served as Deputy Chief Editors: Agranoff, Ansell, Aprison, Bock, Campagnoni, Collier, Eichberg, Miyamoto, Fonnum, Hauser, Ledeen, Martenson, Shooter, Soreq, Walsh and Wolfe.

Chief Editors, after the generative years, were normally appointed for four years. However, given a considerable work-load, it proved difficult sometimes to coerce a successor, so some of the Chief Editors listed in Table 4 had perforce to serve for longer periods. One of the Chief Editors was only able to persuade his successor (Keith Tipton) by plying him with numerous glasses of Guinness in Dublin Pubs! He, in his turn, extended his service to avoid simultaneous change-over of the Chief Editors of the Western and Eastern hemispheres. Those of us who have served in this capacity found it a most enjoyable and rewarding task. The principle of having papers reviewed by two independent referees, and the feeling that authors should be given constructive and encouraging feed-back, made many more friends than enemies, and the exercise kept the Editors well educated in the subject. All of us benefit from good sound refereeing, and most of us would acknowledge the truth that our papers have been substantially improved by the comments of referees and editors. We would encourage our younger colleagues to accept invitations to become editors – it is a good and rewarding expenditure of energy.

As a result of consultations between Derek Richter and Robert Maxwell, the Journal became the property of I.S.N. officially on Jan. 1, 1970, with the agreement that Pergamon should continue to publish it for five years, after which another five years would follow if there were mutual agreement. Maxwell agreed to the principle of transfer of ownership if a formula could be found to reimburse Pergamon for the value of the copyright. This became impossible to estimate in view of the difficulty experienced by the Society’s Officers in assessing profits (see below). One understandable problem derived from the original discussions between the representative scientists and Maxwell : the records of the time show that Derek Richter and Jordi Folch-Pi stated that they did not anticipate a change of publisher (there was no reason why they should, given the harmonious relationships of the time), so in the subsequent litigation, these discussions were interpreted quite differently by the protagonists.

In the new arrangements of 1970 Pergamon agreed to make over 40% of the nett profits to the society – these were not forthcoming and the Treasurer at the time (Brian Ansell) was offered access to the combined accounts of all Pergamon Press journals, but without employing professional accountants (very expensive, and the Society had no money) there was no way he could dissect out those specifically relating to J.Neurochem. In the mid 1960s and again in the 1970s, the production time was very slow (there is much agonised correspondence from the Chief Editors in the archives), and in the late 1970s parts of the journal appeared with pages inverted or missing. The production staff at Pergamon (M. Church and A.N. Richards), with whom we had excellent personal relations, were unable to help due to internal management problems. In private conversations with Mike Church, he was even more frustrated by the problems than we were. The publication problems therefore did not improve despite numerous undertakings by Maxwell, so the Society decided to look elsewhere for a publisher. Interest was expressed by the British Biochemical Society (who published many journals including the highly respected Biochemical Journal), by Elsevier (who published extensively in the Neurosciences) and by Raven (who at that time were active in symposium publications in the Neurosciences). The I.S.N. Council finally decided that the offer from Raven was the most attractive, so signed the contract, for publication to commence in January 1980. After the agreement that the Journal was to be published by Raven, Pergamon continued to advertise J.Neurochem. as its product in its 1980/1981 catalogue, and persisted in billing members and libraries for subscriptions to it. Pergamon then hinted that it might publish a competing journal with the title “The Journal of Neurochemistry” : the subtle distinction between that title and the established “Journal of Neurochemistry” would have caused chaos amongst members, and particularly libraries. (There is a considerable correspondence between Dick Rodnight, speaking for I.S.N., and the Society’s solicitors on this problem, in Sep. 1981, preserved in the archives). Also, Maxwell refused to release the list of I.S.N. members, and subscribers to the journal being published by Raven were being billed to Pergamon, while the legitimate publishers didn’t know who to bill! A further headache for the Publications Committee was the “hostage” manuscripts : some 41 manuscripts had been accepted for publication by the Editors and were in the hands of Pergamon at the time of the changeover of publishers. Pergamon was forbidden to publish them by the court injunction (below) but was reluctant to hand them over to Raven.

On advice from our London solicitors (Adam Burn & Metson), I.S.N. had earlier applied for an injunction to prevent Pergamon from publishing J. Neurochem. in 1980 and to force Pergamon to divulge the subscription list. Les Iversen and I recall spending a considerable amount of fascinating time being briefed with the Barrister (Mr N. Pumphrey of Grays Inn, London) for the forthcoming case which was heard in the Chancery Division of the High Court of Justice in London, December 18-19, 1979. The result was a temporary injunction against Pergamon which read “On the Defendants stating that they have no intention of publishing other than the December 1979 issue of the Journal of Neurochemistry, any of the articles supplied to them by the Plaintiffs and upon the Defendants undertaking to supply within 14 days a list of names and addresses of the subscribers to the 1979 journal, it is ordered that the Defendants be restrained until Judgment in this action, or further Order, from publishing after the December 1979 issue any journal under the title Journal of Neurochemistry or any other title only colourably different therefrom and that the Plaintiff’s costs of these proceedings be cost in cause” (whatever that means!). On a lighter note, those of us who’d been called were fired up to appear as witnesses at this Chancery hearing ( a big event in our relatively peaceful lives), but after the submissions by the opposing barristers (advocates), the court found in I.S.N.’s favour without the need to call on our expertise! An amusing experience (in retrospect) was an informal meeting with Maxwell in Robert Balaz’s office at the Institute of Neurology in London, when Maxwell pleaded for the “jewel in his publishing crown”, and to be given the chance to prove his commitment to improve the quality of the production of the journal. On our observation that his track record on production and finances did not give much assurance for the future, he produced a histrionic performance that would have been the envy of a Shakespearean actor.

Maxwell argued verbally and in letters, with some justification (given the perspective of time which we now enjoy), that he had been shabbily treated by the Society – that “he had founded the journal, had nurtured it through its infancy and developmental period, had contributed significantly to the development of neurochemistry as a field, had generously transferred ownership of the journal to the I.S.N. , and had collected membership dues free of charge”. He requested a one-year extension of his contract to be given the opportunity to demonstrate his willingness to cooperate. On being reminded that I.S.N. could not agree to this, as a contract had been signed with Raven, he then suggested that the journal might be produced jointly by the two publishers. The Publications Committee of I.S.N. acknowledged the service Pergamon had generously provided over the years but felt that their contract with Raven must stand. The differences between Pergamon and I.S.N. were exacerbated somewhat by some rather emotional writing in the I.S.N. Newsletter of Summer, 1980, which gave Maxwell reason to believe his case could be strengthened by accusing the Society of defamation. This was followed by a very strong threatening letter in October 1980 from Pergamon’s solicitors that the “publication of malicious falsehoods and libels” in the Newsletter were “gravely defamatory”. Our solicitors expressed their uncertainty about our chances of a clear victory in Court, much to the concern of our Officers, bearing in mind the then limited financial resources of the Society. The first battle had been won, i.e. to preserve the integrity of the journal and to obtain the subscription list, but the war had been far from won. It should be emphasized that this was a temporary injunction pending a full Court Case which would probably not have taken place until well into 1981. Our Officers were understandably most apprehensive of any ensuing litigation, given the relative poverty than of I.S.N., compared with the infinite financial resources of Maxwell’s publishing empire (the legal costs to I.S.N. had already exceeded $5,000 and were soon to be double that sum). On the advice of our solicitors (who served us well throughout), Elling Kvamme was encouraged to explore the possibility that Maxwell might be prepared to settle out of court. There was much ensuing confidential correspondence between them, which resulted in a reasonable compromise agreement: that Maxwell would make a donation to the Society in return for peace-making statements appearing in the I.S.N. Newsletters, which would separate the cessation of hostilities from his donation to the society. These were accordingly as follows :

Newsletter, March, 1982. “An amicable agreement has been reached between the publisher of Pergamon Press, R. Maxwell, and the Chairman of I.S.N., E. Kvamme, whereby the dispute arising out of the transfer of the publishing arrangements for the Journal of Neurochemistry has been settled out of court. It was agreed that the contract between the two parties has been terminated and that Pergamon Press will not publish a journal under the name of Journal of Neurochemistry, and that the Society agreed to restore its previous good relations with Pergamon and welcomes the publication of Neurochemistry International”. [The stress borne by some of our Officers during these protracted negotiations made them accept the latter part of this compromise statement only with great reluctance].

The understanding between Maxwell and Kvamme was that on the publication of this first item in the Newsletter, Pergamon would make the agreed donation to I.S.N.

Newsletter, Spring, 1982. “It is a pleasure to announce that Pergamon Press has donated a sum of $20,000 to I.S.N., $10,000 to be used by the society in any way it sees fit, the other $10,000 ear-marked for travel”. [This latter donation pleased Graham Johnston immensely as he had long argued for it in his capacity as Chairman of the F.I.S.N., Table 3].

It took some time, and many letters from our representatives before the donation finally came through to Alan Boulton in July 1982. The Society owes much to Elling Kvamme for conducting a series of difficult, diplomatic negotiations with Maxwell, which turned out to be as successful as could be hoped. Our solicitors were very satisfied with the outcome, and in a letter of the 15th July 1982, quoted an old English saying – “He who sups with the Devil should use a long spoon”! Elling Kvamme’s personal recollections of the affair are in the Archives.

It was Brian Ansell as Company Secretary who carried the main burden of the correspondence with Pergamon and our solicitors over the litigation, and who bore the essential stress. The Society owes him an unrepayable debt, and it is tragic that he is not here with us to share in our current prosperity and scientific vitality.

Good relations were quickly restored between members of I.S.N., especially those of the Editorial Board of J. Neurochem., and our colleagues associated with Pergamon Press and Neurochemistry International.

The Journal maintained a sustained growth (Fig. 2), and publication strategies sometimes suffered from its success in that the increase in submissions of good quality papers made it difficult to plan the pagination for the coming year. This explains the “plateaux” of Fig.2. Other episodes in the history of the journal tend to be minor by comparison with the momentous events described above. One recurrent theme has been rivalry between the two Editorial Boards on quality and editorial processing time. It has usually been good-natured, exemplified by comments by Eastern Board editors of the time taken to help non-English speaking authors with their manuscripts – the invariable response from the Western Board editors is “you should read the diabolical English of some of our authors!”

In 1980-1,the “Matters Arising” column was initiated (with some expressions of concern that it might prove divisive) but it seems to have been successful in that the content has proved constructive and educative.

In 1981-2 the Advisory Board was rolled up into the Editorial Board, with the consequent large increase in numbers of Board members, a few of whom were not very active, but who have rotated off since then.

In 1987 Rapid Communications began, with concern over the added work-load for our unpaid truly professional editors. These “Rapids” are universally regarded as eminently successful, and as far as we are aware, our Chief Editors are managing them superbly. Such developments have the inevitable cost implications, and it is to the credit of our Treasurers that they have appreciated the need to give full financial support to these ventures. It’s worth emphasizing that the financial health of the society is directly due to the essentially unpaid efforts and professional integrity of the editors.

In spite of all of these trials and tribulations (or perhaps because of them?) the journal has thrived as can be seen from the growth illustrated in Fig. 2 and to judge from the citation indices for core journals.The latest figures (1991) for the “Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Section of the SCI Journal Citation Reports” are J. Neurochem. 24, just above Biochem. J. at 28, and higher than Europ. J. Biochem. and Biochim.Biophys.Acta. In the “Neurosciences Section of the SCI Reports” , J. Neurochem. stood at 14.

L. Sokoloff W. Sperry

L. Sokoloff W. Sperry

H. Bachelard, A. Boulton, K. Tipton (left to rigth)

H. Bachelard, A. Boulton, K. Tipton (left to rigth)

A. Davison L. Iversen

A. Davison L. Iversen

W. Norton K. Suzuki

W. Norton K. Suzuki

M. Lees G. Lunt

M. Lees G. Lunt

E. Kvamme and H. Bachelard

E. Kvamme and H. Bachelard

Chapter 9 – The Historians and the Archives

The I.S.N. Council decided in 1976 that it was time the society had an historian and asked the Secretary at the time, Jordi Folch-Pi, to take it on. He was formally appointed to the position in 1977 and served the society by writing its first history (Folch-Pi, 1980), and by starting the collection for the archives. After his untimely death in 1979, he was succeeded by Abel Lajtha in 1980, who served in this capacity until 1983, when Henry McIlwain took over.

Henry was then working in semi-retirement and had time to devote to organising the archives in specially designed boxes to ensure their preservation, first at St. Thomas’s in London and then in Birmingham. After his death in 1992, he was succeeded by Gerald Curzon. The main problem Henry encountered arose from the international nature of the society, officers having belonged to different countries and cultures, and operating in different styles. This was reflected in severe problems in securing continuity of records – the three elected officers did not usually have complete sets of the documents created by their predecessors. This sometimes made it difficult to be sure as to the precise decisions taken by their predecessors. Victor Whittaker sought to help Henry in this respect by asking each officer to make an additional copy of every document and send it to the historian to be stored in the archives. Unfortunately their responses were disappointingly sporadic. Admittedly this was sometimes due to reluctance to make contentious or controversial correspondence freely available. Appeals were then made in I.S.N. News and many members responded by sending earlier documents and so most but not all of the key documents have been collected.

The first history session was proposed by Cees Van den Berg and held as a Round Table during the Nottingham meeting in 1981.The session was well attended and proved so popular that on his appointment as historian, Henry McIlwain pressed for regular historical sessions to be part of the I.S.N. Meetings and such have been included all the meetings since then, except for that held in La Guiara (Table 5). The meeting in La Guiara was held jointly with A.S.N. and the organizers felt that the program was too large to accomodate a historical session. In his personal account of the “Post of Historian, I.S.N.”, stored in the archives, McIlwain noted that the success and popularity of the historical sessions was reflected in audiences averaging over 100, even though they ran in competition with current experimental research sessions. It is fitting, though sad, that the historical session held at this meeting in Montpellier, is dedicated to Henry McIlwain and to the French neurochemist, Paul Mandel.

Table 5. Historical sessions held during biennial ISN meetings.

Meeting Title, Organizer Theme

Nottingham

1981 History of neurochemistry

Cees van den Berg

Biochemical studies on behavioural problems

(Andreoli, Ansell, McIlwain, Rose)

Vancouver

1983 History of neurochemistry

Henry McIlwain Various : Hensing and phosphorus, energy metabolism, axoplasmic

transport, ideas on drug action (Ansell, McIlwain, Ochs, Tower, v.d.Berg)

Riva del Garda

1985 History of neurotransmitters

Brian Ansell & Henry McIlwain Personal recollections of participation in studies on identification & function of transmitters (Blashko, McIlwain, Rapport, Richter, Vogt, Weil Malherbe)

Algarve

1989 Contributions to early neurochemical

development by drugs and

medicaments, 1850-1950s

Henry McIlwain As title (Curzon, McIlwain, Sandler, Sourkes, Whittaker)

Sydney

1991

Influences on the development of neurochemistry

Henry McIlwain

Technical developments, the history of neurochemistry revealed by papers published in J.Neurochem. (Curzon, Lathja, McIlwain, Whittaker).

Chapter 10 – The Future

It is interesting, and at first sight surprising, that over the years the numbers of active participants at our bienniel meetings have remained static at around 700-900 when membership numbers and the growth of the subject have been steadily increasing. The reasons for this may be partly related to the fact that the numbers of scientific meetings have multiplied to the extent that we have to be increasingly selective in deciding which meetings to attend if we are to spend any time at the bench.